While the need for new antibiotics is urgent and should naturally attract investors, there is too little innovation and R&D in the field of antibiotic resistance. We are facing what is known as a market failure, the main reason for which is linked to the need to preserve their value for public health. Indeed, the consumption of antibiotics has a private, short-term value for each patient, but it also has an impact on the population as it promotes the development of antibiotic resistance. To take this externality into account, the aim of healthcare systems will be to reduce antibiotic consumption in order to preserve their effectiveness and only use them as a last resort. This means that manufacturers launching new antibiotics on the market could only expect small sales volumes. High sales prices would therefore be necessary to ensure profitability. However, sales prices are low because it is too risky for regulators to approve high prices for drugs with no immediate side effects and no out-of-pocket costs, which manufacturers would then have an incentive to promote. This combination of low prices and low volumes explains the lack of investment in innovation in new antibiotics.

Solution #1

One possible solution that has unfortunately not been used so far would be to require the use of a diagnostic test for any use of antibiotics, for which very high prices could then be paid for effective innovative antibiotics. This would require the authorities to commit to very high prices and strict regulation requiring the use of tests. This type of regulation would stimulate innovation efforts against antibiotic resistance by enabling the industry to invest more in diagnostics and antibiotics. Without this joint regulation of mandatory diagnostics allowing the use of very expensive innovative antibiotics, the market value of innovations against antibiotic resistance will remain too low to generate innovation.

Solution #2

An alternative to this regulation is to disconnect the innovator’s remuneration from the quantities sold by promising a fixed reward for the inventors of an innovative antibiotic that would be available and usable as a last resort.

Thus, the idea was put forward to offer a sufficiently large reward to any innovator who could find a cure for multi-resistant bacteria. The difficulty lies in establishing an incentive that is sufficiently significant. The United Kingdom recently launched a pilot programme, but this type of initiative faces the problem of free riders. Since innovation is a public good, no country will want to pay for it alone, but each country has an interest in minimising its potential contribution, which makes it impossible to finance innovation. This result has been demonstrated by Moisson, Dubois and Tirole (2023).

Solution #3

An alternative is to use transferable exclusivity extensions or vouchers, which could be implemented by the European Medicines Agency and whose principle was proposed by the European Commission in the new medicines legislation of 26 April 2023.

With such a system, innovators receive extended intellectual property rights for the development of a new antibiotic. They can use it themselves or sell it to the owner of a highly profitable drug (a blockbuster) whose patent (and therefore period of exclusivity) is about to expire, thereby delaying the arrival of equivalent generic drugs. At the European level, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) could be the regulator of these vouchers.

The advantage of this mechanism is that it applies to every country that uses this other medicine. Of course, this means that the medicine benefiting from extended exclusivity is sold at a high price for a longer period of time. This mechanism therefore has a social cost, since it is financed by the healthcare system of each country.

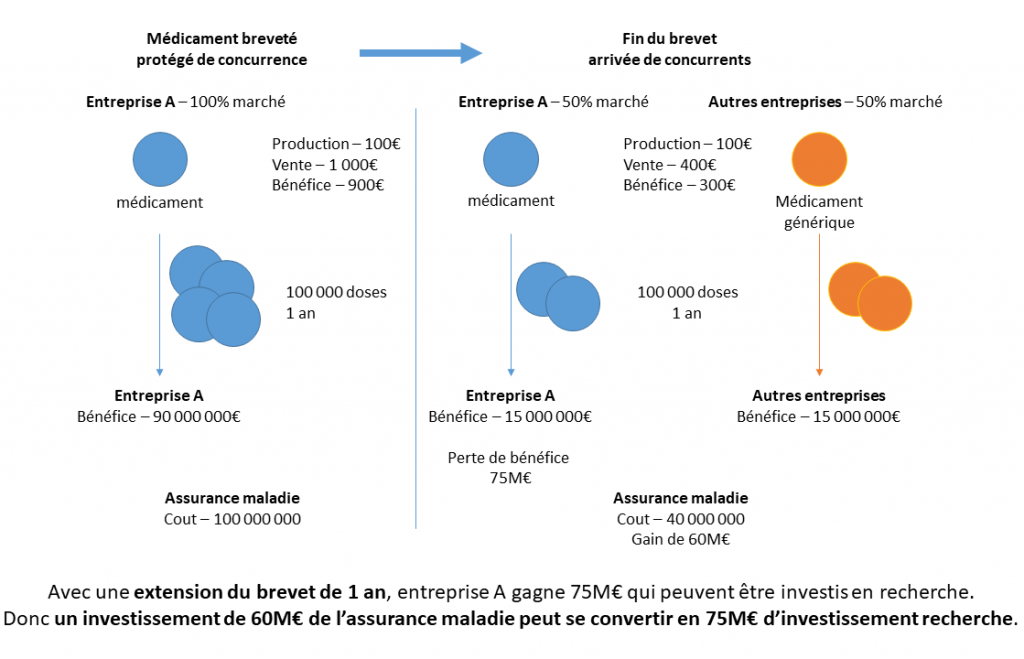

However, Dubois, Moisson and Tirole (2023) compared the cost/benefit ratio for the community of remunerating innovators in the form of vouchers versus traditional direct reimbursement in various European countries. This comparison shows that the cost of vouchers is generally lower due to the margin on generic drugs and the cost of public funds. Let us take the simplified example (Figure 1) of an innovative drug with a marginal production cost of €100, sold for €1,000 while its patent protects it from competition. With a market of 100,000 doses per year, the originator company therefore makes a profit of £90 million per year, at a cost to the health insurance system of £100 million. When generics enter the market, assuming they acquire a 50% market share and the price becomes €400 per dose, the profits of the original manufacturer fall to £15 million and those of the generic manufacturer are also £15 million, at a cost to insured persons of £40 million. In such an example, the originator company would therefore be willing to pay up to 75 million to extend the drug’s exclusivity by one year. This is the amount that an innovator holding a transferable extension of exclusivity could charge a profitable patent holder, which would finance €75 million in R&D at a cost to society of £60 million, since the 100,000 doses of the drug would cost £1,000 instead of £400 for an additional year.

The system is therefore beneficial both politically, in terms of aligning all European countries in a common direction, and in terms of the efficiency of public spending.

In practice, instead of setting a period of extended exclusivity (transferable) as a reward for an innovator, it may be preferable to reward them with a fixed voucher amount (sufficient to encourage investment in the fight against multi-resistant bacteria, for example), which will be auctioned between the innovator and pharmaceutical companies: the one offering the shortest period of exclusive market maintenance will be selected.

References

Dubois, Moisson, Tirole (2023) « L’économie des prolongations de brevets transférables » mimeo

Dubois, Moisson, Tirole (2023) « Les extensions de brevets transférables peuvent-elles résoudre la défaillance du marché des antibiotiques ? » https://www.tse-fr.eu/sites/default/files/TSE/documents/HealthCenter/2022-11_transferable_patent_extensions.pdf

Moisson Paul-Henri, Pierre Dubois, Jean Tirole (2023) “The (Ir)Relevance of the Cooperative Form”, TSE Working Paper, n. 23-1453, June 2023.

Autor

Pierre Dubois

Professor of Economics

Toulouse School of Economics