It is now common knowledge that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a social problem that must not only be studied as a biomedical challenge, but for which other factors – i.e. sociological, economic, political and cultural determinants – must be taken into account. Most research into social factors has been conducted from a social psychological and behaviourist perspective, but it tends to overlook the structural and organisational determinants that provide the framework for individual behaviour. It is precisely these structural determinants (public policies, markets, professions, technologies, etc.) that the teams working on the Digital Observatory of Antibiotic Resistance (DOSA) and the STATIC project, funded by the Antibiotic Resistance RPP, are looking at.

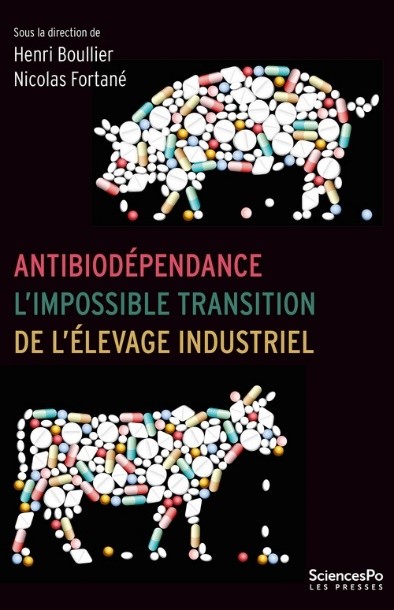

The work carried out by our social science research teams provides valuable material for documenting what we have called Antibiodépendance (Boullier and Fortané, 2025), to use the title of a book published this year by Presses de Sciences Po. The book is the result of research carried out between 2019 and 2024 by a dozen sociologists, historians and political scientists, both as part of the PPR and previous projects. Using the example of the use of veterinary antibiotics, they show that the agri-food system and the actors who dominate it deploy a series of strategies not only of resistance but also of resilience, which allow the system to change only marginally.

The mechanisms of anti-biotic dependence

The surveys show that the agri-food system is deeply and structurally dependent on the use of antibiotics. As soon as these drugs appeared, they revolutionised the sector, with the development of intensive livestock farming in closed buildings, characterised by high levels of antibiotic use. Since then, as these surveys illustrate, the system has had great difficulty in changing. At the dawn of the 2000s, numerous regulatory measures were put in place to reduce the use of antibiotics in livestock farming. Farming practices have changed and antibiotic consumption in farm animals in France has clearly fallen, but many uses (curative, metaphylactic, growth promoters in imported meat, etc.) persist. The antibiotic infrastructure has managed to maintain itself, and even become more indispensable than ever. Our analyses show how the contemporary agri-food system is not only antibiotic-dependent, but also antibiotic-resistant: as measures to reduce the use of antibiotics have been adopted, the industrial model has adapted.

While the investigations reported in this book focus on the case of veterinary antibiotics, the more general approach to the problem of AMR reveals a production-based system that remains in place despite the damage it causes to human societies and the environment, beyond the strict confines of industrial livestock farming. In human health, talk of the misuse of antibiotics overlooks the fact that they are often used as a means of avoiding more serious social problems. Surveys carried out by colleagues in public hospitals in Bangladesh (Biswas et al., 2020) show that pharmaceutical companies push doctors to prescribe antibiotics, but that it is above all the failings of the healthcare system that lead practitioners to use them: staff shortages at all levels, departments overwhelmed by the influx of patients, hygiene and sanitation problems, etc. In contrast to behaviourist approaches that focus on individuals, patients or doctors, on their personal biases or deviances, this work invites us to take account of the socio-economic and political factors that explain the use of antibiotics and that may contribute to AMR; it invites us to think about antibiotic dependence in a context of health system failure.

Like the surveys carried out by our group, these studies suggest that the rise of AMR is largely fuelled by the use of antibiotics as a quick fix for structural problems (Willis and Chandler, 2019). On the one hand, this use is supposed to provide a (sometimes approximate) medical response and maintain the productivity of individuals and, more broadly, of living organisms. It is a rapid response, and easier to implement than preventive policies, to pathologies and patient demands in a context of ‘pharmaceuticalization’ of society. On the other hand, as Willis and Chandler point out, antibiotics make it possible to “manage” problems of hygiene and poverty without really solving or repairing them. These drugs are used to get people back to work or school more quickly in the event of infections, when a period of rest would be more appropriate (in a ‘cure’ rather than ‘care’ perspective). Antibiotics have thus become tools for maintaining inequalities in global health policies, and are alternately rationed to avoid “irrational” use and widely prescribed to put living organisms to work, which resonates with the system of antibiodependence at work in intensive livestock farming.

Ways out of antibiotic dependence.

Even though our agricultural and health systems often use antibiotics as a quick fix, the surveys contained in the book identify several ways out of antibiotic dependency. The first would be to move away from the anthropocentrism and latent Westernocentrism of global policies to combat AMR. The respective aporias of “One Health” and “Global Health” tend to reproduce injustices and inequalities between humans and animals, and between North and South. At present, animal health in “One Global Health” is concerned only with the health interests of humans, and a fortiori those of Western societies, and ignores the food and development issues facing producer countries in the South. It seems essential to change the current vision of the problem and its solutions, and in particular to move away from the idea of a threatening South and a threatened North. In reality, the biggest consumers of antibiotics remain, by far, Western societies, while the vast majority of deaths linked to resistant bacteria occur in the southern regions of the globe. The problem of ‘excess’ is in fact opposed to that of ‘access’ (Chandler, 2019). In some cases, the best way to prevent the emergence and/or spread of resistant bacteria, while at the same time effectively managing the infections they cause, is precisely to improve the availability of medicines.

A second avenue to explore concerns the involvement of patients who are victims of AMR and taking an interest in their experiences. At present, health professionals and international health experts are the ‘owners’ and main audiences of the problem. It is defined by them and for them. Patients, on the other hand, i.e. the people who experience resistant bacterial infections on a daily basis, remain inaudible and invisible. This is illustrated by the almost total absence of coverage of the subject in the major national media. This invisibility is linked to the fact that AMR is not a disease quite like any other. In fact, it is not a disease as such. Rather, it is a microbiological and pharmacological characteristic (with major health and social consequences) that certain infectious diseases may or may not have. It is likely that a large part of the difficulty patients have in identifying with the term stems from this. Nobody “has” AMR. On the other hand, you can have a resistant urinary tract infection, ultra-resistant tuberculosis or multi-resistant pneumonia. Perhaps these voices should be heard in order to learn about the intimate, family, social and medical experiences of people suffering from resistant infections. It is by telling these stories, as the non-governmental organisation The AMR Narrative or the members of the WHO AMR Survivors Task Force are doing, for example, that we can do more to encourage recognition of patients and their mobilisation in the fight against AMR.

A third approach would be to transcend the dystopian imaginary that accompanies discourse on AMR. Like other health and environmental issues, AMR is caught up in a catastrophist narrative that tells the story in terms of drama and catastrophe. It seems impossible to imagine a world without antibiotics other than through a nightmarish or warlike narrative. Is it possible to imagine a desirable world without antibiotics? A diversion via the English language may be useful in breaking out of the prevailing dystopia: a world without antibiotics is not a world without antibiotics but an antibiotic-free world, in other words a world freed from antibiotics or, more accurately, from dependence on antibiotics. To be free of antibiotics, AMR must not be reduced to a medical and safety issue, but must embrace issues of social and ecological justice such as access to healthcare, hygiene, food safety and quality, environmental protection and the preservation of biodiversity (plant, animal and microbial). A world without antibiotics is not the apocalypse of a war lost in advance against bacteria, but a world freed́ from a structural dependence on medicines too often used as a quick fix. We need to imagine a new utopia and build it as quickly as possible.

Références :

1 Biswas Debashish, Hossin Raduan, Rahman Mahbubur, Bardosh Kevin Louis, Watt Melissa H., Zion Mazharul Islam, Sujon Hasnat, Rashid Md Mahbubur, Salimuzzaman M., Flora Meerjady S., Qadri Firdausi, Khan Ashraful Islam et Nelson Eric J., « An ethnographic exploration of diarrheal disease management in public hospitals in Bangladesh: From problems to solutions », Social Science & Medicine, vol. 260, 2020, p. 113185, [https//doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113185].

2 Boullier Henri et Fortané Nicolas, 2025, Antibiodépendance. L’impossible transition de l’élevage industriel, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po.

3 Chandler Clare I. R., 2019, « Current Accounts of Antimicrobial Resistance. Stabilisation, Individualisation and Antibiotics as Infrastructure », Palgrave Communications, 5 (1), p. 53, https//doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0263-4.

4 Willis Laurie Denyer et Chandler Clare, 2019, « Quick Fix for Care, Productivity, Hygiene and Inequality. Reframing the Entrenched Problem of Antibiotic Overuse », BMJ Global Health, 4 (4), p. e001590, https//doi.org/10.1136/ bmjgh-2019-001590

Authors

Henri Boullier

CNRS sociologist and scientific coordinator of the STATIC Junior Chair of the PPR Antibioresistance Programme

Nicolas Fortané

INRAE sociologist and scientific coordinator of the DOSA structuring project of the PPR Antibiorésistance programme.